Beer & Book Showcase | The Two Hendricks: Unraveling a Mohawk Mystery

Eric Hinderaker’s The Two Hendricks Unraveling a Mohawk Mystery discusses two men during the eighteenth century who played significant roles towards maintaining the Iroquois Confederacy amid a French-English rivalry regarding their mutual goal to control North America. Their history, somewhat hidden within broader narratives, at one point included a belief the two were only one person. Hinderaker discusses each men’s lives while also informing how the two men’s history merged (as well as why that could not have been possible). The elder took a trip to London and met the Queen. The younger met with several prominent British colonials. The discussion of both men’s lives provides a lens into the Anglo–Iroquois alliance, notably as it pertained to their place within the British – French struggle.

The Beer

Taddy Porter | Samuel Smith

Not only has Samuel Smith been around since the British interacted with the Hendricks in North America, but the beer is comprised of well water from its original well, dug in 1758. Given that the elder Hendrick traveled to London, one can imagine that people who first drank Samuel Smith might have known about the Mohawk leader’s visit to London. If not, it’s still fun to imagine. The porter is a classic and almost needs no description. The recipe consists of malted barley, roasted malt, yeast and hops. And, as it Samuel Smith notes, the beer is “fermented in ‘stone Yorkshire squares’.” How perfect given that the Hendricks lived in “New York.”

View this post on Instagram

The Book

The Two Hendricks: Unraveling a Mohawk Mystery

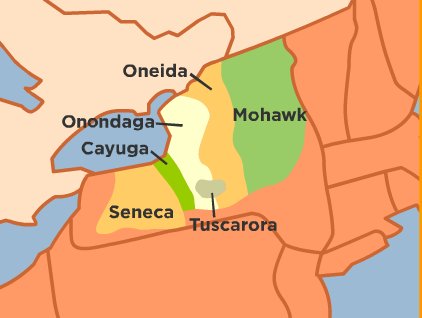

Both Hendricks lived as high-profile members of the Mohawk nation, which existed as the eastern-most tribe within the six-nation Iroquois Confederacy. They both played significant roles in their relationship with Euro-Americans, especially Britain. Although early Iroquois culture celebrated war, both Hendricks were baptized as Christians, thus came to believe strongly in the benefits of peace and diplomacy rather than warfare as a means of handling Mohawk affairs. The French and British hoped to align with the Mohawks, both understanding that a principal means of gaining favor with the Mohawks involved gift-giving — a sign of trust. (And, the Hendricks both used the French-British rivalry to their advantage.) The European rivals sought an alliance with the Mohawks, but both Hendricks decided to side with the British.

The first Hendrick – Hendrick Tejonihokarawa – was a sachem from the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk tribe. During the late seventeenth century, he rose to power and aligned with the British despite many of his peers preferring a French alliance. In 1690, he was baptized into the Dutch Reformed Church and subsequently adopted a Christian name: “Hendrick.” He formed a strong bond with the Dutch Reformed ministers and many prominent Albany citizens, including New York colonial governor Edmund Andros, which came to be known as the Covenant Chain. The relationship grew so strong, in fact, that Tejonihokarawa and three Mohawk leaders accompanied six colonial officials on a trip to London in 1710. While there, the London High Society referred to Tejonihokarawa Hendrick as the “Emperor of the Six Nations.” He even received an audience with Queen Anne and sat for a state portrait per her request.

Hinderaker argues that the London visit demonstrates Hendrick’s appreciation of the British and, in turn, the British’s respect for Hendrick; they viewed a relationship with Hendrick as the source of stability regarding the British presence in North America.

Hendrick Peters Theyanoguin, the second (younger) Hendrick (and also baptized by Dutch reformers), made his first formal appearance, Hendricks argues, in 1741. By that point, the Six Nations had enjoyed years of peace forged by the elder Hendrick, Tejonihokarawa. However, that peace came with decreasing trading activity between the Mohawks and the Brits. Instead, the North American British colonists chose to trade with the French illegally. So, the younger Henrick exploited that illegal trading network for Iriquois gain. He used his knowledge to push the English in Albany to not only re-establish their covenant with the Six Nation Confederacy but provide them with sizable gifts. As a result, Hendrick Peters Theyanoguin gained substantial power in the Six Nation Confederacy. Although Theyanoguin never received an invite to London like the elder Hendrick, he rubbed shoulders with British elites and colonial officials in New York, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania.

The firm bond created by the second Hendrick came with an agreement to mutually fight against the French during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). However, “King Hendrick” died at the start of the war, the first step in ending the alliance created by Tejonihokarawa Hendrick almost 70 years earlier (and the U.S. Independence secured its end).

For years after the two passed away, the Hendricks’ history slowly merged into one story, which also became hidden within the broader narrative. Above all else, the book reminds us that Native Americans were not just simpletons or savages. They were intelligent human beings and enjoyed enough clout that the French and English vied to develop relationships with them. The Hendricks’ story helps humanize the Mohawks and provide a new perspective to the story of the British-American colonies.

Submit a Comment