Beerology | What Makes Beer Sour?

Welcome to Beerology! Once a month, we will take a look into the origins of all things booze. In this edition of Beerology, we are going to dive into the world of sour beers. Despite the extreme increase in number of breweries producing sour beer, there has not been an increase in knowledge for consumers. So, we’re making an effort to thwart misinformation. Read on to learn the basics of what makes beer sour.

If you’re someone who thinks that Americans created sour, let’s do a real quick crash course in the history of Lambic. What’s Lambic? Only the most important beer style that has led to the sudden explosion in number of “sour” beers on shelves across the country. Lambic is a spontaneously fermented beer that is produced in a region of Belgium called Pajottenland. In a nutshell, spontaneous fermentation is the process of inoculating wort with wild yeast and bacteria present in the brewery’s environment and letting those microorganisms have sole responsibility over fermentation, no added brewer’s yeast or commercial cultures. This is the most traditional way of creating acidity in beer and is the predecessor to modern production of sour beer.

Before we dive into the various processes of creating acidity in beer, let’s go over a few important terms.

Mash

Think of “mashing” like making oatmeal. Crushed malt is mixed with hot water and left to stand. In the mash, the conversion of grain starch into sugar occurs. These sugars will become “yeast food,” meaning they are fermentable and are responsible for creating alcohol in beer.

Wort

The sweet liquid that is pulled from the mash once the starches have been converted to sugar. This sugar water is boiled, cooled, and then placed in a fermentation vessel where yeast is then pitched to begin the process of fermentation.

Fermentation

“Brewers make wort, not beer. Yeast makes beer,” writes Randy Mosher in Tasting Beer. Once the wort is cooled and placed in the fermentation vessel, yeast is pitched into the liquid. Yeast metabolizes the sugars (that were converted from grain starch in the mash process) and creates ethanol (alcohol) and carbon dioxide (carbonation), in addition to many other chemicals that we will not go into here.

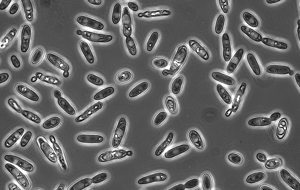

Brettanomyces

The literal definition of Brettanomyces is “British brewing industry fungus.” In 1904, N. Hjelte Claussen, laboratory director at Carlsberg brewery at the time, discovered a microorganism that caused a slow, secondary fermentation in English stock ales. While Brettanomyces is a slow-growing yeast, it is also a superattenuating yeast, meaning it will continue to slowly consume sugars for many years. This type of yeast is extremely important to the production of “wild” beers. Brettanomyces is characterized by earthy, “horsey” aromas and a dry mouthfeel in beer.

Lactobacillus

Considered a “facultative anaerobe,” Lactobacillus can ferment both with or without the presence of oxygen. As a byproduct of fermentation, lactobacillus produces both carbon dioxide (carbonation) and lactic acid, which lends a tart, tangy character to beer. Lactobacillus has little to no aroma of its own.

Pediococcus

Considered a “microaerophilic,” Pediococcus will not ferment in the presence of oxygen and grows much slower than Lactobacillus. Also unlike lactobacillus, Pediococcus does not produce carbon dioxide (carbonation). Pediococcus ferments glucose into lactic acid and is responsible for the bulk of the lactic acid production in traditional Lambic. A byproduct of Pediococcus in beer fermentation is Diacetyl, a buttery/butterscotch aroma and slick mouthfeel. While acceptable in small doses in some beer styles, most brewers hope that Diacetyl will be broken down during fermentation. Little known fact: If given enough time, Brettanomyces can break down even high levels of Diacetyl in beer.

Alright, now let’s dive in to the various processes of creating sour beer.

Sour Mash

This technique involves adding acidity prior to primary fermentation by introducing lactic acid bacteria to the mash. After the standard mash rest, the mash is cooled to around 120°F and is inoculated with the bacteria Lactobacillus. In order to prevent unwanted microbes that can possibly spoil the mash, a brewer must ensure that the mash stays at an incubation temperature of 120°F for the entirety of the sour mash. Each brewery has its own timeframe for sour mashing, which can last anywhere from 12 hours to multiple days. Once the mash has reached the desired acidity (pH), the wort is separated from the grain and the brewing process continues from boil to fermentation.

Examples: Black Shirt Brewing | Sour Mash Red Saison (update, BSB has now retired the sour mash process and are focused on mixed culture and wild inoculation, see further down for an explanation of that process), Lagunitas Brewing I HotSide Sour Mashed Daytime

Kettle Sour

The brewing process for kettle sour is business as usual until all wort is collected in the boil kettle. Brewers will bring the wort to a boil then chill to a desired temperature, usually between 80°F and 120°F, and inoculate with Lactobacillus bacteria. Once the desired acidity (pH) is reached, the wort is boiled to kill off the Lactobacillus. Some brewers will boil the wort normally while others will just raise the temperature of the wort to 170°F for several minutes to reach pasteurization and ensure there is no additional Lactobacillus activity.

Examples: Breakside Brewing | Bellwether, Westbrook Brewing Co. | Gose

Mixed Culture Fermentation

Let’s start by looking at the most important word in this classification of souring: fermentation. In this process, the brewery makes wort as usual, puts it in the fermentation tank (stainless tank or wood barrels/foeder), adds in the necessary bugs and let them do work! What do we mean by bugs? The classic combination is a mixed culture of Brettanomyces (wild yeast), Lactobacillus (bacteria), and Pediococcus (bacteria), which work together to create funky aromas and acidity.

Examples: Casey Brewing & Blending | Saison, Crooked Stave | Origins

Spontaneous Fermentation

This process is similar to Mixed Culture in terms of the souring occurring after the wort has been produced. However, instead of the more controlled fermentation with Mixed Culture, spontaneous fermentation relies on natural yeast and bacteria that floats through the air. Brewers that practice spontaneous fermentation, utilize a koelschip (coolship) to inoculate their wort. After the boil, wort is poured into the koelschip, where it is left to, well cool, usually overnight so that wild yeast and bacteria have a chance to take up residence and begin the fermentation process. This is the most traditional way of creating a sour beer – this is how all Belgian Lambic is created. If you want to learn more about all things Lambic, check out Lambic.info.

Examples: Allagash Brewing | Coolship Resurgam, Cantillon… all of them

Sources

Daniels, Ray. Designing Great Beers. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2000.

Sparrow, Jeff. Wild Brews: Beer Beyond the Influence of Brewer’s Yeast. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2005.

Suggested Readings

Farmhouse Ales: Culture and Craftmanship in the Belgian Tradition by Phil Markowski

Wild Brews: Beer Beyond the Influence of Brewer’s Yeast by Jeff Sparrow

-

Wouldn’t the literal meaning/definition of Brettanomyces just be ‘British fungus?’

Comments