Book Review & Interview | The Homebrewer’s Almanac

The Homebrewer’s Almanac: A Seasonal Guide to Making Your Own Beer from Scratch (Countryman Press, 2016) by Marika Josephson, Aaron Kleidon and Ryan Tockstein

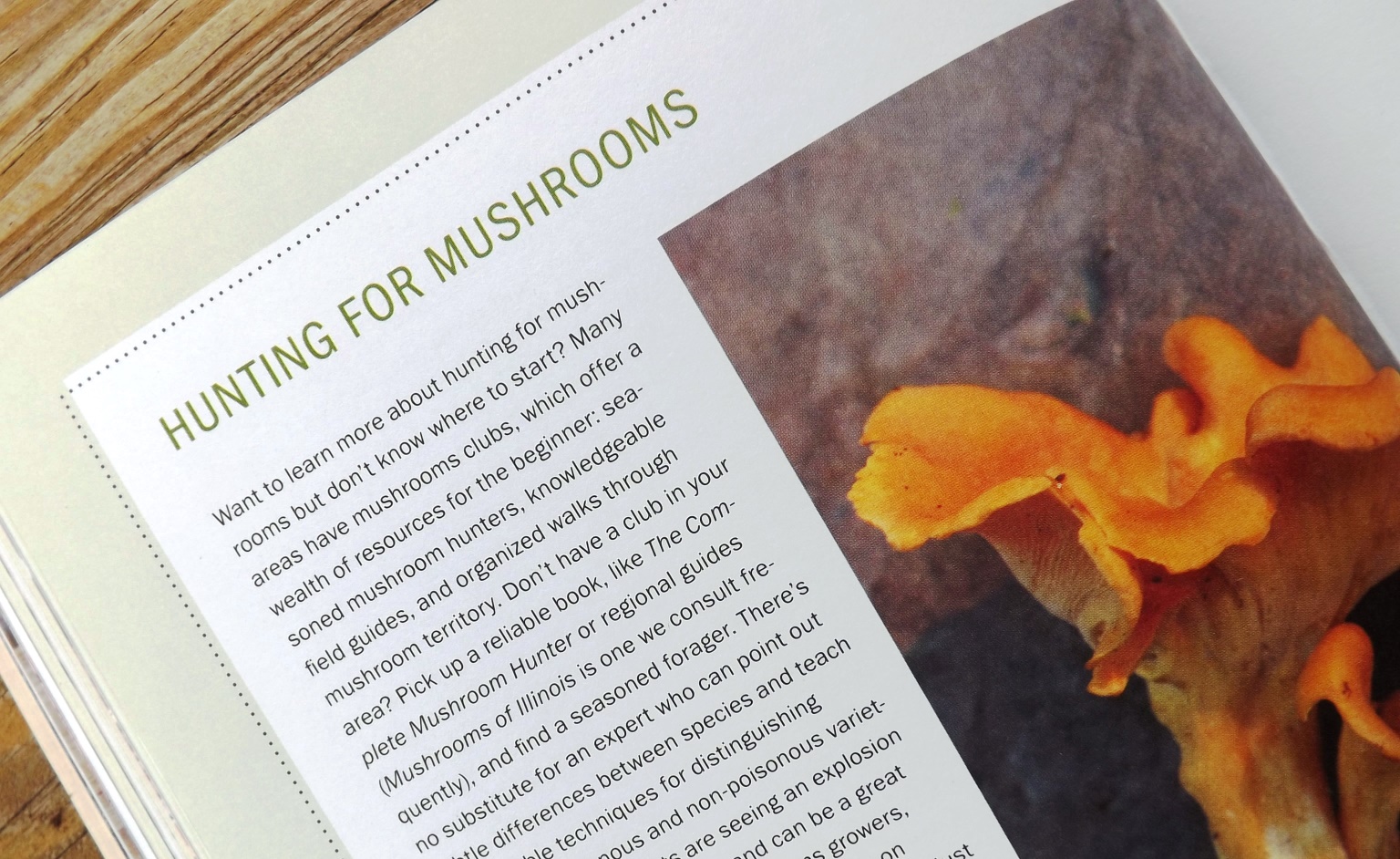

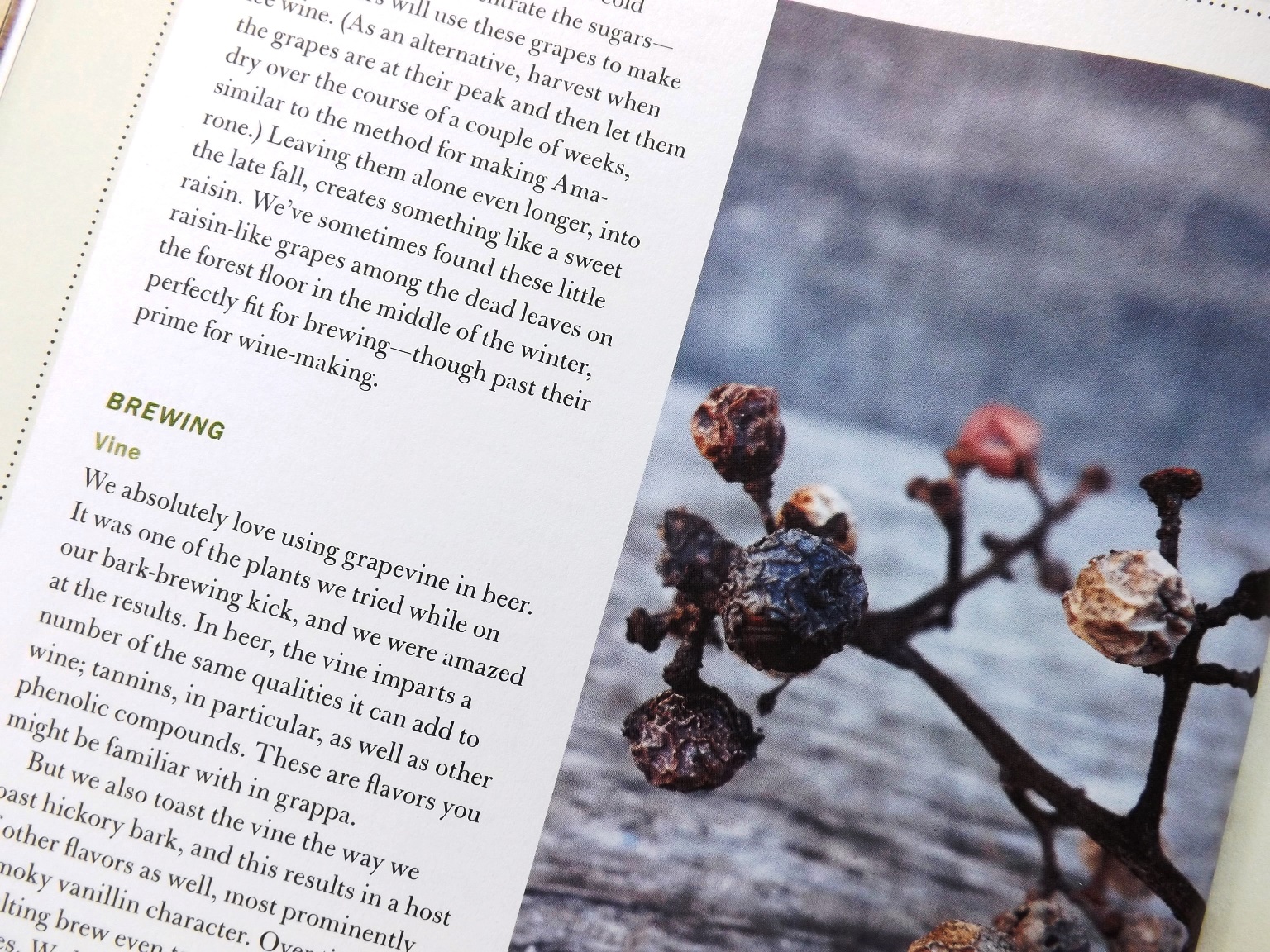

The folks at Scratch Brewing Co. are connected to the land around their brewery in ways few other brewers can boast. Secluded in the woods near Ava in southern Illinois, the Scratch gang doesn’t just use local malt and hops, they pull the ingredients that make their beers so unique from the terrain of the surrounding forest. Tree bark, leaves, mushrooms, berries, nuts, flowers, even plants many of us have been trained to think of as weeds—it’s all fair game for brewers Aaron Kleidon and Marika Josephson. Consequently, their beers have a quality of place—terroir, to use the fancy parlance—few other brews have.

In a spirit of true rural hospitality and helpfulness, Kleidon, Josephson and Ryan Tockstein (who co-founded Scratch but has since departed) have written a book that helps homebrewers better understand how to brew beer with foraged ingredients. The Homebrewer’s Almanac: A Seasonal Guide to Making Your Own Beer from Scratch is an invaluable book for homebrewers (or professional ones, for that matter) who want to go beyond the basics and start crafting beers that are deeply connected to the particular climate and landscape they call home.

“The woods enchant us: every pine sapling with its outsized needles, every fallen oak tree and its mushroom denizens, every bitter green leaf and tannic root, every paw paw hidden beneath the fall leaves. The three of us spend a lot of time in the woods—not just to make beer, but because the woods speak to us. We take its pulse; we respect its force. It has a special language we sometimes hear and more rarely speak.” (Preface, page ix)

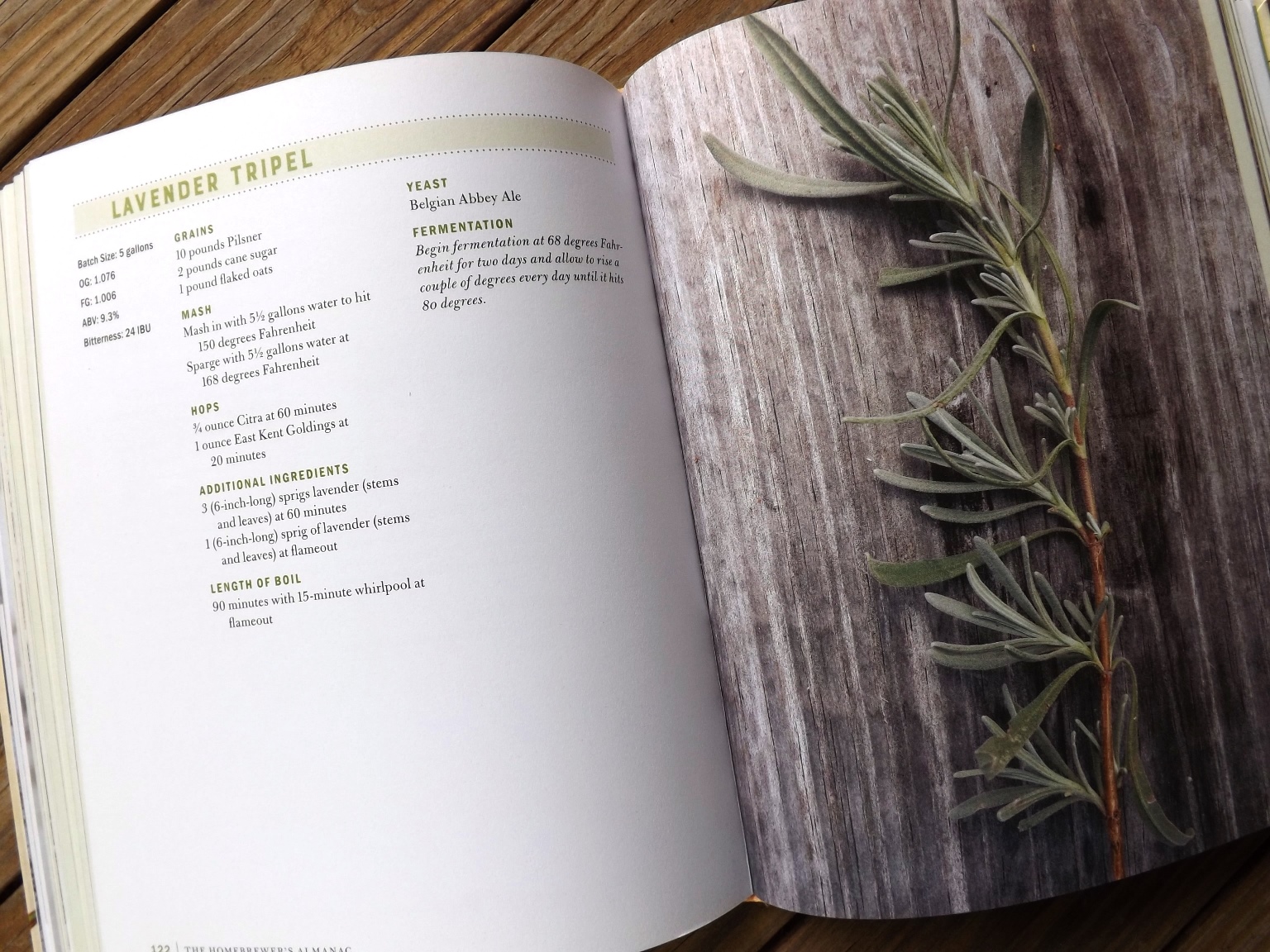

The Homebrewer’s Almanac is not a guide to beginner’s homebrewing. The authors assume readers are coming to this book already possessing the basic knowledge needed to brew. The book instead focuses on when, where, and how to forage for particular ingredients, and how to utilize them during the brewing process. The book is divided into the four seasons, with each section containing chapters on the foraged ingredients Scratch is most fond of brewing with during those times of the year. The book, like the beers at Scratch, is tied by necessity to the resident flora of southern Illinois, so this won’t be a one-stop source on foraging for every area of the country. The authors provide enough general guidance however that you should be able to adapt the principles they outline in the book to wherever you go scouting for beer ingredients. The book also includes dozens of recipes for recreating Scratch beers. Experimentation is encouraged.

“Our dos and don’t list in pretty short, but it will always produce palatable beer:

DO care about sanitation and fermentation temperature.

DON’T care about calculating IBUs.

Everything else can be approximated.” (Introduction, page xviii)

This is more than just a how-to brewing book though. This book is a worthwhile read even if, like me, you don’t homebrew. The book is beautifully illustrated with numerous full-color photographs, and the authors’ graceful prose makes this an excellent read for anyone who wants to better learn the connection between local landscapes and climates and the beers that are brewed from them. While reading this book, I felt like I was walking through the woods with the authors on a crisp fall day, smelling the leaves and soil and trees, rooting through the underbrush for ingredients, fingers chilled and damp.

I recently had the chance to speak with author and brewer Marika Josephson about The Homebrewer’s Almanac and the blend of innovation and tradition she and the Scratch team are brewing up in the Illinois woods. After you read the interview below, check out the Scratch Brewing website and order a copy of this excellent book.

First off, tell me a little about the philosophy and practice behind what you’re doing at Scratch. It’s not your typical brewery.

Scratch may be atypical for modern industrial breweries and the modern industrial food system but it would have been a typical farmhouse brewery in the past, one in which brewers were making beer with native ingredients that grew in unique parts of the world. We wanted to create a brewery that had a sense of place, that smelled and tasted like Southern Illinois, and that celebrated regional and agricultural diversity.

How did the Scratch folks get started with foraged beer? Was this always the plan, or did it just develop that way?

Aaron and I, in particular, had been experimenting extensively with brewing with locally grown ingredients as home brewers. I was scouring the farmer’s markets and he was playing around with plants in the forest. We were reading a lot of the same books and were jazzed about a lot of the same ideas for making beer. We didn’t really create the brewery to make “foraged beer,” per se; we created the brewery because we wanted to incorporate regional plants and products, and since we’re surrounded by the woods it only made sense to include those things as well.

We looked at a number of locations to build and for one reason or another they fell through. The brewery may have ultimately been different if we’d decided to build in the center of a more populated urban area or even a small town. But once we decided for good to build a brewery in the woods it became more obvious that the woods should take center stage in our beer. That was more or less when we decided we wouldn’t have any “flagship” beers and that the brewery would truly be centered around the seasons, and therefore around what nature would offer us at any given time.

In The Homebrewer’s Almanac, you give the reader such a beautiful sense of place. I could imagine myself in the Illinois woods and fields as I read. Can you talk a bit about how foraging for ingredients and writing about it for this book ties you to the specific geography—the climate, flora, and fauna—of the place you live and work?

For me, writing helps me clarify my thoughts, and sometimes even helps me understand subconscious feelings I haven’t otherwise articulated. Aaron (who did the photographs for the book) always talks about how it’s easier for him to create photographs of places that he feels a deep connection to, places where he’s spent a lot of time in and knows the landscape or people well. I think the book is a natural output of our connection to this place and creating the book even helped us to articulate some of the things we express in beer without words.

What has the response been so far from the homebrewing community (or commercial craft brewing community) to your book and the brewing practices you describe in it? Do you have a lot of people trying out these techniques and telling you about their attempts?

We actually wanted the title to be simply “The Brewer’s Almanac” because we didn’t want people to think it only had information for home brewers, or that homebrewers were any less curious, informed, or even accomplished than commercial brewers. We at Scratch started as home brewers and many of the styles and processes we’re inspired by and come from regional farms and beers made in basements and barns for families or small communities.

For that reason, it’s been fantastic to see the book cross over between home brewers and commercial brewers. We’ve met a number of people who have told us that they have a brewery in planning and that they’re hoping to incorporate local ingredients in a similar way and that our book has helped and inspired them. Nothing could be more rewarding than to hear that.

We’ve had pretty close contact as well with our local home brew club, the Southern Illinois Brewers, and with a handful of home brewing friends who tried recipes in the book and have given us feedback. I was able to try a few early experiments from our home brew club members and tweaked some of the recipes as a result. I love getting feedback via email or social media and answer all of the inquiries we get from home brewers who are working on recipes and have questions.

What was the process like for writing The Homebrewer’s Almanac? I imagine it could be challenging taking these intuitive skills and understandings you’ve gained and translating that into a prescriptive guide for others.

We gave ourselves a year to create the book so that we could go through an entire cycle of seasons and take notes and photographs. That way we could record sights and tastes and smells throughout the year, and keep track of some of the small details about harvesting and preparing plants. Once you’ve done something a number of times you often forget how to describe how to do it from beginning to end so it helped to have a year’s worth of time to take notes. We are also bad sometimes about weighing ingredients. A lot of our recipes are “a handful” of this and “three sticks” of that! So we tried to get more precise to help people recreate what’s been successful for us.

It’s currently mid-Summer. What are you foraging right now and preparing to brew? Do you have a favorite season for what you’re doing?

We’re in the middle—heading toward the end—of fruit season. We just added blackberries to our Blackberry Lavender beer, peaches to our Freestone, and are planning some fun experiments with apples for the fall. Pawpaw season comes like clockwork the first week of September so we try to keep on top of that. Basil is taking over our garden so we’re working that into beer. We just passed chanterelle season but didn’t harvest enough to make a batch of beer this year, unfortunately. The Chanterelle Biere de Garde is one of our favorites but so dependent on the whims of the seasons. We won’t have one this year.

I understand part of your team recently went to Belgium. How was that trip? What was the response like there to your beer?

Aaron and I represented Scratch at the Leuven Innovation Beer Fest this summer and it was a fantastic festival. It’s hosted by Hof ten Dormaal, a beautiful farmhouse brewery located just outside of Leuven, only a half an hour or so from Brussels. Their aim was to create an intimate festival with a small number of breweries doing innovative things with beer and gave festival goers most of the day to try the beer. You have enough time and brain power to sample just about every beer there and talk to the brewers themselves—and what an amazing collection of people and ideas. Most of the people there were Belgians and we were glad to find that they enjoyed our beer and the philosophy behind it.

So many “farmhouse ales” today are rural and agrarian in name only. They might be great beers, but they’re often brewed in urban breweries alongside mainstream craft styles and are only distantly related to the true farmhouse ales of old. It seems that foraged beers like Scratch brews are one of the last avenues in the craft scene toward a true agrarian brewing tradition in twenty-first century America. Is that an intentional push on Scratch’s part? Do you see yourselves pioneering a new farmhouse brewing tradition?

I’d like to see the word “farmhouse” paired more again with breweries that are actually cultivating or harvesting ingredients on site—or nearby—that go into their beer. It doesn’t matter to me if those ingredients are cultivated by farmers or foraged in wild spaces. There is an ironic disconnect in craft beer in which drinkers care a lot about beer being made locally but don’t know or don’t care where the ingredients themselves are actually from. The problem is that farmers are fighting big industrial ag the same way craft brewers have fought big industrial beer and we need to support small farming the same way we’ve needed to support small brewing if we want to see healthier, more diverse, and more flavorful crops. For me, beer is just another kind of food, just another part of the food system, and deep principles that I have with respect to food production are part of our philosophy of beer making—principles I wish more people cared about. Robbing the term “farmhouse” from farms does a real disservice to farmers.

Finally, if homebrewers and beer drinkers take one thing about beer from reading The Homebrewer’s Almanac, what do you hope that is?

This country is diverse; this world is diverse—that’s part of the spice of life. There are hundreds of ingredients hiding in every corner of the globe that can add interesting, unique flavors to beer, it just takes a little hunting and a little experimentation. Go explore!

Submit a Comment