Together Is Not Always Better: How Consolidation In the Middle Tier Is Impacting The Future of Craft Beer Brands

For most craft breweries, the trajectory of brand growth follows a somewhat traditional path – starting with taproom sales, progressing to selling in the wholesale channel, and then alignment with a beer wholesaler to grow the distribution footprint. Sounds simple enough on paper, but if you drill down into the nuances of selling beer wholesale, things get complicated very quickly. The US is unlike any other country in the world when it comes to the three-tier alcohol distribution system. Some states do not allow suppliers to self-distribute (sell directly) their products to licensed retail accounts, yielding asinine practices like selling beer to yourself for your own taproom. Some states are also dubbed “franchise” law states where if your brand aligns with a distributor you must endure a contractual arrangement that makes changing distributor partners harder than selling beachfront property in Arizona. And we haven’t even begun to address the large big beer elephant in the room and how many large beer distribution houses are aligned with one of two big players in the US beer market. For many craft brands that are just getting started or fall into the category of small to medium-sized producers, strategizing how to enter the wholesale channel is a formidable challenge, including contending with a host of other legislative, litigious, and anti-competitive issues in the middle tier that have surfaced over the past few decades. As if growing craft beer producers didn’t have enough to contend with these days in the form of rising costs of goods, labor shortages, inflation, and the squeeze from alternative beverage choices in the marketplace, woes like wholesaler consolidation, unfair trade practices, and antiquated beverage alcohol regulations are making the middle tier the next big battleground for craft beer brands.

The Franchise Conundrum

In 39 out of 51 states, craft beer brands can self-distribute their products in some way, which is usually determined by their annual production output. 16 states and the District of Columbia require all brands, regardless of size, to use a wholesaler to distribute their products to licensed retail accounts. 47 out of 50 states also have some kind of franchise law in place to regulate the distribution of craft beer products, with 13 of those 47 having some form of exclusions for smaller producers. Beer franchise laws were enacted to “correct the perceived imbalance in bargaining power between brewers (who are presumed to be big and rich) and wholesalers (who are presumed to be small and local)” as stated by Marc Sorini, General Counsel for the Brewers Association in his Beer Franchise Law resource guide. To spare you some of the legalese, franchise laws basically lay out responsibilities for suppliers and wholesalers in a contractual partnership agreement, which includes very specific exit strategies for both parties if things are not working out so well. In states where franchise laws reign supreme, it becomes extremely difficult for craft brands to separate themselves from their wholesale partner if the relationship is not a successful one. “Just cause” is a term to familiarize yourself with if you live in one of these states. Terminating partnerships for “just cause” could range from brand abandonment to unpaid invoices from your wholesaler, but could also pertain to mergers and acquisitions amongst wholesalers, but the bottom line is that “just cause” is extremely difficult to prove, with many contracts requiring extensive paper trails of refusal to sell your products or extreme lack of performance on the part of your wholesaler. This is also accompanied by legal fees and lost sales, as most contracts allow for a performance improvement plan aspect that could tie your brand up for anywhere from 60 days to 6 months. And at any point in time, your beer wholesaler could also be acquired or “bought out” by another wholesaler, most of the time being a larger distribution parent company that has ties to a non-independent, macro beer brand. When this happens, the wholesaler is obligated to inform the supplier of changes in ownership, brands, and/or territories and the supplier usually has the choice to stay in place contractually with that distributor or find another one. The easy-button answer is to stay put for most craft brands, but this decision comes with a high risk – being pushed to the back of the line in terms of brand priority, refusing to order product inventory or even getting released by the new parent company.

Supplier Disadvantages

So why would a distributor merger or acquisition be bad for craft beer brands? Reasons that smaller suppliers are getting the short end of the stick include getting removed from the distribution portfolio altogether by the new management team (AKA being released), losing mind share to bigger brands that will be entering the portfolio, losing traction in national accounts due to distribution management changes, losing smaller retail accounts due to new order minimums put in place or automated ordering systems utilized by the wholesaler, and for those in franchise states, having to deal with fewer routes to market because there are fewer distributors to choose from. Now it’s also time to address that big beer elephant in the corner. For all the talk in recent years about beer brand consolidation, craft breweries should also be concerned about how that trend translates into the middle tier. In a 2020 article by Ron Knox for Slate magazine, he states “Despite the popularity of craft beer, the two global beer titans have managed to maintain their grip on the industry largely by influencing how beer is distributed and what is found on store shelves. Almost 90 percent of beer sold in most places in America is handled by distributors whose primary customer is one of the two big brewers, giving AB InBev and Molson Coors outsize control over which beers appear on bar taps and in retail coolers” (Slate 2020). In this type of situation, smaller producers are forced to take a backseat to larger brands when it comes to distributor sales share of mind. And if you’re locked in place by franchise laws, you have no other choice but to take it on the chin or invest thousands of dollars to illicit a release from that wholesaler through legal means. While craft brewery mergers and acquisitions have historically made headlines and drawn more attention than distributor consolidation, it’s what lurks in the shadows that should strike fear into the hearts of any supplier producing less than 15,000 BBLs.

A side note here about large brands being woven into the fabric of the distribution tier – something for everyone in the industry to keep an eye on is the role that traditionally non-alc brands will play in upcoming years as beverage category lines get crossed with entrants to the market like Hard Mountain Dew and Beast Unleashed. The purchasing power of beverage brands like PepsiCo and Coca-Cola is beyond what the craft beer industry could ever imagine. If these two behemoths wiggle their way into the alcoholic middle tier, what’s occurring right now will be peanuts compared to the challenges growing craft beer brands will face when it comes to distribution capabilities and competition on the shelf. “The entrance of one of the world’s largest soft drink companies into the distribution business has created tension with traditional beer wholesalers, many of whom see Blue Cloud as both a practical and existential threat to the status quo” as stated by Kate Bernot for Good Beer Hunting (Good Beer Hunting, October 2022).

The Depth of Consolidation

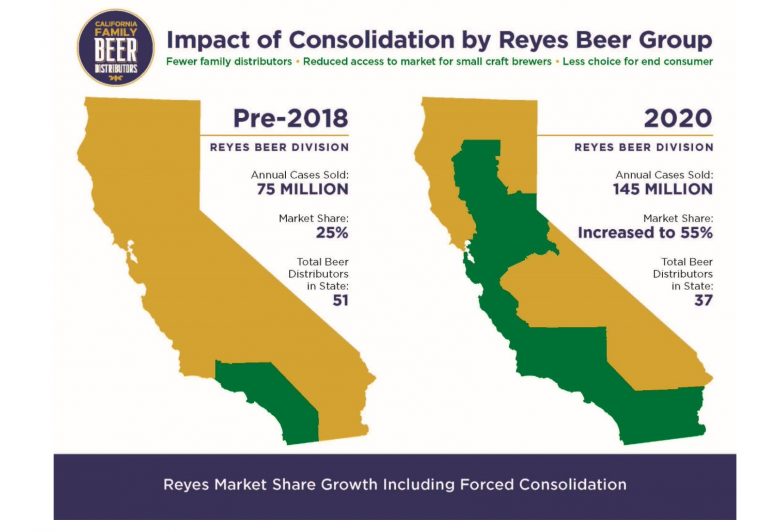

According to the National Beer Wholesalers Association, there were more than 4,500 traditional beer distributors operating in the U.S. in 1980. Today, there are about 3,000. Between January 2022 and April 2023, there were 18 different beer wholesaler mergers or acquisitions, which can all be found by tracking the news wire from Brewbound in their Mergers and Acquisitions feature. 6 of these deals involved a few key players that have been wheeling and dealing for decades – Reyes Holdings, Breakthru Beverage, Southern Glazers Wine & Spirits, and Republic National Distributing Company (RNDC). Reyes Holdings sits at #7 atop the Forbes List of Top Privately Held Companies in 2022 with revenues north of $35 billion, over 30K employees, delivers over 1.2 billion cases of food and beverage products, and is responsible for distributing brands such as Constellation, Molson Coors, Lagunitas, Mark Anthony Brands, Sierra Nevada, Boston Beer, Heineken, and Diageo, in addition to an array of other craft beer brands. In a November 2022 article by Jess Infante for Brewbound, she cites research from Beer Marketers Insights stating that more than half of the beer sold in California flows through the Reyes network (Brewbound 2022).

The situation in California has gotten so dire that a new advocacy group was formed by members of the independent beer distributor community to have a stronger voice in the state trade association. The California Family Beer Distributors (CFBD) met for the first time in November of 2022 to discuss being the voice of reason for wholesalers that are not part of the Reyes network by speaking out about monopolization of the middle tier. Kevin Luckey, the executive director of CFBD, said “We’re concerned about consumers’ ability to get the products they want moving forward if we’re not a highly competitive three-tier system” (Brewbound 2022). If larger distributors hold the keys to the gate for consumers to gain access to more brands, craft beer producers will face more barriers to entering the market and competition will be reduced on the shelf. And that’s not good for anyone. Though you can’t just single out Reyes as the only culprit – Southern Glazers Wine & Spirits sits at #11 atop the same Forbes list at $25B in annual revenue, RNDC comes in at #34 with $12B in annual revenue, and Breakthru Beverage holds steady at #76 with over $6B in annual revenue (Forbes 2023).

Who’s in Charge?

Unless you’re in the craft beer industry or adjacent to the alcohol marketplace at all, then Executive Order 14036 addressing competition in the beer, wine, and spirits industry probably flew under your radar. The Biden administration issued this EO back in July of 2021 to draw attention to unfair trade practices, consolidation, and competition issues in the beverage alcohol industry in order to benefit consumers by laying the groundwork for a more competitive marketplace that would yield better selections of brands and better prices. This request for information was led by the US Treasury Department and the results will supposedly be used to alter regulations across various government agencies to help balance competition and curb consolidation. In a February 2022 article for Food & Wine Magazine, Mike Pomerantz states “Specifically, the Treasury found that consolidation was problematic, complaints were numerous, and many current regulations are likely hurting smaller producers more than the big ones” (Food & Wine 2022). Pomerantz goes on to explain the biggest issue is that the government isn’t doing anything currently to prevent consolidation and is part of the problem. “[Federal regulation] may be more effective if the regulators are charged with enforcing clear rules rather than licensing, approval, and permitting schemes,” the report states in its final paragraph. “The former puts the agency in an oversight role where officials are motivated to enforce the rules (to protect consumers, competition, and public health), while the latter involves arrangements unique to the industry that are more susceptible to being used to suppress competition and to giving an advantage to large, more deep-pocketed entities.” Or to paraphrase an old horror film trope: the call is coming from inside the federal government (Pomerantz, Food & Wine 2022). Unfortunately, most craft bev alc brands know how hard it is to get a straight answer about what’s right and what’s wrong when it comes to alcohol regulation, with many living in fear that if they do ask questions unfair attention will be drawn to their own business practices. All the while, big brands are getting bigger and pushing the boundaries of what’s legal to gain a competitive advantage over historically trending craft brands. Yes, these large corporations and wholesalers get knicked and endure fines for illegal trade practices, but when you’re cranking out billions in revenue each year, getting pinged for a few thousand dollars is a drop in the bucket. And so the cycle continues until the federal government can figure out a way to intervene in a more efficient way.

But That’s Not All

In addition to middle-tier consolidation being a pressing issue, beer wholesalers these days are also not immune from other problems that are plaguing the industry. Employee turnover in the beer distribution industry has been high in recent years due to burnout from Covid conditions and career changes to other industries, including wine, spirits, and cannabis. The lack of bodies has led to lower levels of customer service at the retail level, switching accounts to tell-sell systems or online ordering portals, or even instituting order minimums for retail accounts that don’t order as often, all of which contribute to buyer frustrations and suppliers questioning their distribution partnership agreements. To add insult to injury, wholesalers have also made headlines recently for violations of antitrust laws, franchise reform litigation, falling short with product deliveries, and additional scrutiny brought to unfair trade practices. This leaves many producers feeling like they are in a no-win situation.

Devil’s advocate

For as many concerns as the craft beer industry should have about the current state of the middle tier, suppliers should always remember that the three-tier system that is in place is probably our best bet and that beer distributors are not your enemy. You need them just as much as they need you – for logistics, sales, and service that you yourself as a smaller provider might not be able to provide or shoulder financially. Wholesalers are masters of logistics, route planning, inventory management, and product delivery so you don’t have to be. Yes there are antiquated regulations that the US government needs to address and yes there will always be a corruption of some kind in a capitalistic environment, but that doesn’t mean that smaller producers should lose hope. This is why trade associations like local state or regional guilds, advocacy groups, and larger trade associations like the Brewers Association exist so that the voices of the people on the street can be heard in the form of lobbying efforts. If you want to see reform in the middle tier, craft brands would be wise to mourn today and activate tomorrow.

-

Julie,

Excellent work. I’d only suggest that as far as the three-tier system is concerned, I can’t see any justification for requiring craft brewers to sell via wholesalers. This mandate in many states really needs to go. Moreover, The limited exemptions that allow small brewers to self-distribute need to be less limited and where discrimination exists (allowing in-state brewers to self distribute but barring out-of-state brewers from doing the same thing), that needs to end too. Really great artricle!

Comments